Is the Linux /usr Directory an Abbreviation for User?

The butterfly effect created by a hardware incident 50 years ago

When you use Linux or Unix systems, you’ve probably wondered at least once.

"What on earth does

/usrstand for?"

At first glance it looks like it’s just User minus the e.

If that were the case, why not just call it /user? Why insist on /usr?

- Is it because typing is a hassle?

- Was there a character limit?

- Yet directories like

/boot,/home,/procare all four letters long.

If it really meant “user”, we would have written /user. The ambiguous choice of /usr hides a history we don’t know.

Today we’ll unravel the 50‑year‑old, bittersweet hardware story that ties into this /usr directory—something every developer will nod to and say, “Ah… that explains it.”

1. The Bottom Line: Today’s /usr is NOT “User”

In the current Linux Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS), /usr is defined as:

A global area for read‑only programs, libraries, and shared data

That’s why the structure looks like this:

/usr/bin– most user‑level executables/usr/sbin– system‑administration executables/usr/lib*– libraries used by those executables/usr/share– architecture‑independent data such as manuals, icons, and locales

It’s far from “personal user files.” Home directories (~/…), documents, photos, etc., all live under /home.

So, from a modern perspective, we can define /usr in one line:

/usr= “Not a User, but the OS and apps’ shared system‑resource warehouse.”

That leaves one question:

“Wasn’t

usroriginally an abbreviation for user?”

That’s where the fun begins. Its origin was indeed “user.” But over the past 50 years, its usage flipped completely.

2. Early Unix: /usr/username Was the Home Directory

Let’s rewind to the early 1970s.

At that time, a Unix system’s home directories weren’t /home/alice as we know them today. They were directly under /usr, e.g., /usr/alice.

So back then, /usr truly meant:

“A directory for user‑related things.”

The machines were PDP‑11s, and disks were unimaginably small—just a few dozen kilobytes or megabytes. The structure made sense:

- Root disk (

/) – a tight space holding only the core OS files - Second disk (

/usr) – a relatively generous space where user home directories lived

This layout was rational. The problem? Unix (and its developers) grew too fast.

3. “Disk Full” → Move System Files into /usr

Unix kept expanding, adding new commands and features. The catch was that the root disk (/) capacity stayed the same.

One day the reality hit:

“There’s no more room on

/for programs…”

Developers made a pragmatic choice:

“The second disk (

/usr) is spacious, so let’s move non‑essential programs there.”

Thus, what began as a user home directory slowly became a dumping ground for programs, libraries, and data.

The result is the structure we know today:

/bin– essential boot commands (originally on the root disk)/usr/bin– the rest of the commands (migrated to the second disk)/libvs./usr/libfollows a similar logic

In short:

The original user house,

/usr, became a system‑file storage simply because it had spare space.

It’s a classic “disk‑space‑driven hack.”

Later, as Unix evolved:

- Home directories moved to more intuitive places like

/home /usrsettled firmly as the shared program/library area

The irony is clear:

- Name:

usr(user) - Content: system and app files

The owner moved out, but the house is now full of system files.

4. “Unix System Resources”? That’s a Later Coinage

This paradox persisted long enough that someone coined a new meaning:

“Let’s call

/usran abbreviation for Unix System Resources.”

You may have seen documents that say “/usr = Unix System Resources.” The key point is:

This is a backronym—a later, retroactive interpretation, not the original intent.

Early Unix documents and testimonies show:

/usrwas originally user- It housed

/usr/usernamehome directories - Disk‑space constraints pushed everything else into

/usr

Over time, people simplified the narrative:

“Now that

/usrholds system resources, let’s call it Unix System Resources.”

That’s a classic backronym: an acronym that’s retrofitted to fit an existing word.

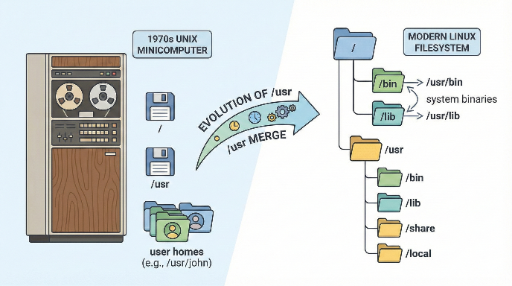

5. From 50‑Year‑Old Structure to Today: The Usr Merge

You might wonder:

“If disks are now plenty, why keep

/binand/usr/binseparate?”

Modern Linux distributions (Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, etc.) are actively cleaning up this historical legacy—the /usr merge (UsrMerge).

Try running this on a recent distro:

$ ls -l /

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 7 ... bin -> usr/bin

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 7 ... sbin -> usr/sbin

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 7 ... lib -> usr/lib

Most systems will look like this.

/binis a symbolic link to/usr/bin/sbinand/libare similar

So the current real structure is:

“Most programs and libraries live entirely under

/usr.”

Why merge? Several reasons:

- Simplifies package management and porting

- Makes container/ISO images easier to treat as a single system image

- No longer necessary to maintain the old split due to modern hardware limits

The fascinating part is that all of this traces back to a 1970s decision to cram programs into /usr because disks were tiny.

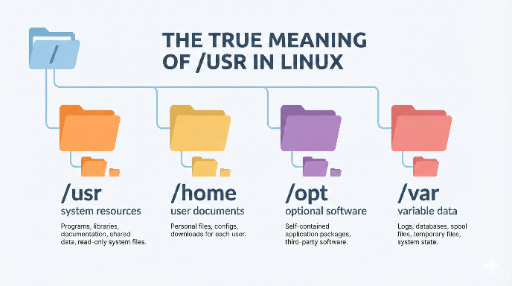

6. How Should We Think About /usr Today?

When working with a Linux system, keep this in mind:

“

/usris the shared area for programs, libraries, and shared data.”

Conversely:

- Personal files / settings →

/home/your_account - Frequently changing data (logs, cache, DBs) →

/var - Apps installed outside the distro’s package manager → usually under

/optor/usr/local(Ask Ubuntu)

So:

/usr= OS and app world/home= User’s personal world

This distinction reduces confusion.

In Closing: The Story Behind a Directory Name

Inside /usr lies:

- The pragmatic concerns of early Unix developers facing disk‑space limits

- The “let’s do this now, tidy up later” mindset

- The decades‑long standardization and cleanup effort (UsrMerge)

Rather than simply memorizing:

- “

/usr= Unix System Resources” - “

/usris not a user directory”

Understanding this background gives you a richer perspective when you see /usr/bin or /usr/lib in the terminal.

“Ah, that’s the result of a 50‑year‑old disk‑space hack.”

Even a single directory in a black terminal holds the legacy of hardware limits and developer compromises—quite fascinating, isn’t it?

There are no comments.