The True Identity of the /usr Directory in Linux Filesystems

usr is not a user

If you’ve ever used Linux, you’ve inevitably encountered the /usr directory.

When I first started using Linux, I thought:

“Ah,

/usrmust be for users. It probably contains stuff related to user accounts.”

Many beginners probably had a similar misunderstanding at least once. But let’s get straight to the point:

/usris not a directory for individual “user” data. The home directories are handled by/home, while/usrserves a completely different purpose.

In this article, we’ll clarify the real identity and role of /usr, and explain how it differs from other directories such as /home, /opt, and /var.

1. Bottom line: /usr is not a “user data” directory

In modern Linux, the role of /usr can be summed up in one sentence:

/usr= the area where the system stores “shared, (generally) read‑only) programs, libraries, and data.”

In plain terms, it contains:

- Executable binaries for the OS and applications

- Libraries used by those executables

- Shared resources such as manuals, icons, and data files

Conversely, the files you typically think of as “user‑specific documents, settings, downloads” live under:

/home/<username>

They serve a completely different purpose. So thinking of /usr as a “user directory” is simply wrong.

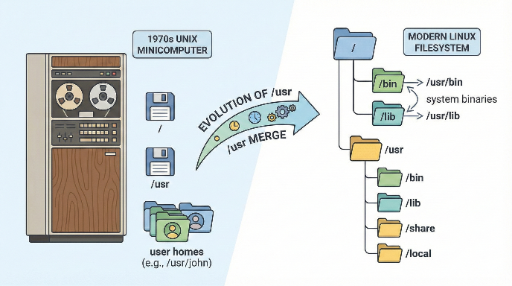

2. What does usr stand for?

There’s a bit of history and debate here.

- In early Unix,

/usractually contained user home directories. - Hence the traditional view that

usris a contraction of “user.” - Later, it was reinterpreted as “Unix System Resources” or similar.

But for modern Linux users, the historical spelling is less important than the current role.

The Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) defines /usr as:

- A place for data that can be shared system‑wide (read‑only, if possible)

- Programs, libraries, manuals, and shared data

So, whether usr stands for “user” or not is largely irrelevant. The key takeaway is:

It’s a shared resource area for the system and applications.

3. What lives under /usr?

If you run ls /usr on a server or desktop, you’ll usually see directories like:

$ ls /usr

bin lib lib64 local sbin share include ...

Each directory roughly means:

/usr/bin– Binaries for regular users (e.g.,/usr/bin/python,/usr/bin/grep,/usr/bin/curl)./usr/sbin– System‑administration binaries, typically used by root (e.g.,/usr/sbin/sshd,/usr/sbin/apachectl)./usr/lib,/usr/lib64– Shared libraries used by programs (e.g.,.sofiles)./usr/share– Architecture‑independent shared data (man pages, icons, locale data)./usr/include– C/C++ header files used by development toolchains./usr/local– Space for programs installed locally, not via the system package manager.

In short:

/usris a big warehouse of system‑wide programs and related resources—executables, libraries, and shared data.

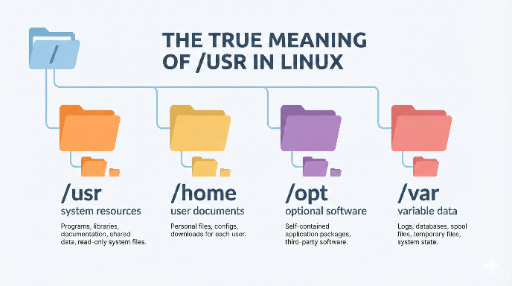

4. /usr vs /home vs /opt vs /var — what’s the difference?

Linux filesystem structure can be confusing at first, especially when comparing /usr, /home, /opt, and /var. Here’s a quick comparison:

4.1 /home — the real “user” house

- Example paths:

/home/alice,/home/bob - Per‑user data: documents, photos, downloads, project folders

- User‑specific settings:

~/.config,~/.ssh, etc. - Even after reinstalling the OS,

/homeis often preserved.

Personal data and settings = almost all in

/home.

4.2 /usr — shared resources for the system and apps

- Binaries:

/usr/bin,/usr/sbin - Libraries:

/usr/lib* - Shared data:

/usr/share

“Everything the whole system shares” =

/usr.

No individual user files belong here.

4.3 /opt — a place for a single app bundle

- Non‑distribution‑packaged commercial or third‑party apps often live here.

- Example:

/opt/google/chrome,/opt/mycompany/app - The pattern is usually one directory per application.

“This app lives entirely here” – an application‑level management space.

4.4 /var — data that changes (Variable)

- Logs:

/var/log - Cache:

/var/cache - Queues, spools:

/var/spool - Databases, state files, and other frequently changing data

“Run‑time data” =

/var.

5. Why is it /usr/bin instead of /bin? (And it’s even more confusing today)

Older documentation explains why /bin and /usr/bin were separated. Modern distributions simplify this by making:

/bin→ symlink to/usr/bin/sbin→ symlink to/usr/sbin

So on current systems:

- Most executables live under

/usr/binand/usr/sbin /binand/sbinare essentially legacy placeholders for backward compatibility.

For newcomers, this can be confusing, but the core idea is:

“Where are the actual programs?” → Mostly in

/usr/binand/usr/sbin.

6. How to avoid confusion as a beginner

The typical confusion when first using Linux looks like this:

- “

/usris for users, right?” - “Should I install my program in

/usr?” - “What’s the difference between

/homeand/usr?”

Remembering a few simple rules usually clears up most confusion.

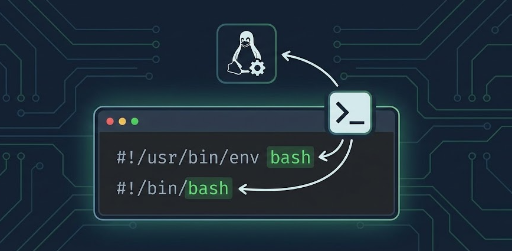

6.1 Where to put personal scripts/tools?

- Personal scripts or tools: usually

~/binor~/scripts - Add to

PATHif needed:

mkdir -p ~/bin

echo 'export PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"' >> ~/.bashrc

This is a personal space, distinct from /usr.

6.2 Where to put system‑wide custom apps?

- Compile from source or install third‑party apps (AppImage, tar.gz)

- Common pattern:

- Main executable: under

/opt/<appname> - Launchers: symlink to

/usr/local/bin

This keeps the system tidy.

Thus, /usr/local is conventionally:

“Space for programs not installed via the distribution’s package manager, managed locally.”

It’s more natural to think of /usr/local as a dedicated area for administrators to use at will rather than a sub‑area of /usr.

7. Summary: /usr is a “system warehouse,” not a “user’s house”

Let’s recap:

/usris not a user data directory.- In modern Linux,

/usrcontains: - Shared executables

- Libraries

- Shared manuals, icons, data

- A large, read‑only warehouse for the system and applications.

- Personal data lives under

/home/<username>. - Custom-installed apps usually go to

/optor/usr/local.

Once you grasp the filesystem structure, you’ll naturally answer questions like:

- “Where should I place this file?”

- “Is this app for the whole system or just me?”

- “What should I preserve when reinstalling the OS?”

Understanding /usr correctly is a solid starting point.

There are no comments.