Linux AppImage: One‑File Desktop App Distribution

When you install a program on Windows, you usually think of the following steps:

- Download an

.exeor.msiinstaller. - Click “Next, Next, Finish.”

- You rarely know exactly where files end up (registry entries, scattered files, etc.).

Linux offers a completely different, almost unheard‑of distribution method on Windows: AppImage.

Just as a single APK runs an app on mobile, a Linux AppImage lets you run a full desktop application with one file only—no installation, no package manager, just a single executable.

In this post we’ll cover:

- What an AppImage actually is.

- Why it feels unfamiliar yet appealing to Windows users.

- How to manage AppImages on Linux, especially under

/opt.

What is an AppImage?

In one sentence:

AppImage = a single executable that bundles an app and all its required libraries.

It packages everything an application needs into one file and distributes that file as a standalone executable.

Using it is trivial:

# 1. Download the AppImage

$ ls

MyApp-1.0-x86_64.AppImage

# 2. Make it executable

$ chmod +x MyApp-1.0-x86_64.AppImage

# 3. Run it

$ ./MyApp-1.0-x86_64.AppImage

That’s it. There’s no “install” step, and if you want to remove it, just delete the file.

Compared to Windows, it’s similar to a portable app, but AppImage is a standard format for the Linux desktop ecosystem.

Why Windows users find it unfamiliar

Traditional Windows installers:

- Copy files to system folders.

- Add registry keys.

- Register start‑menu entries, services, drivers, etc.

The user ends up with a lot of hidden changes across the OS.

AppImage, on the other hand:

- Has no registry.

- Doesn’t touch system directories.

- Isn’t registered with a package manager.

It exists as a single, self‑contained file that can live anywhere and still run.

If Windows feels like “I have no idea what’s installed on my machine,” AppImage shows “I have exactly this app here” at the file level.

This aligns with Linux philosophy:

- Everything is a file.

- Prefer user‑understandable structure over magical installs.

AppImage offers the simplest model: app = one file.

Advantages of AppImage

1. No installation process

- No package‑manager registration.

- No hidden copies to

/usr/bin,/usr/lib, etc. - No registry.

Just a single executable.

2. Easy removal

- Delete the file when you’re done.

- No lingering system changes.

Configuration files may still appear in ~/.config, but the binary itself is always visible.

3. Avoids dependency hell

AppImages usually bundle the libraries they need, so:

- Different distributions may ship different glibc or

libXxx.soversions. - The AppImage can handle these differences internally.

Users can be more confident that the app will run on their distro.

4. No root required

Typical workflow:

- Download.

chmod +x.- Run.

No need to copy files into system directories, so no sudo is necessary.

Trade‑offs with package managers

AppImage isn’t a silver bullet. Common drawbacks include:

- Centralized management is hard – you can’t see all AppImages from a single UI.

- Update mechanisms vary – some AppImages ship an updater, others don’t.

- Disk space – each AppImage contains its own libraries, leading to duplication.

Therefore, it’s best used for:

- Apps that are difficult to install via a package manager.

- Applications you want to run on multiple distributions.

- Experimental or niche tools.

Where to store AppImages? Management strategy

Let’s tackle the practical question: where should I keep my AppImages?

Two common approaches:

1. Keep them in your home directory (~/Apps, ~/bin, etc.)

- No root privileges needed.

- Works fine for a single‑user machine.

Drawbacks:

- Not shared across users.

- Can become confusing if you have many AppImages.

- Blurs the line between personal data and system applications.

2. Organize under /opt by application

This is my preferred method.

- Create a directory under

/optfor each app. - Move the AppImage there.

- Set appropriate permissions and optionally create a symlink in

/usr/local/bin.

Example for MyApp.AppImage:

# 1. Create app directory

sudo mkdir -p /opt/myapp

# 2. Move the AppImage

sudo mv ~/Downloads/MyApp-1.0-x86_64.AppImage /opt/myapp/myapp.AppImage

# 3. Make it executable

sudo chmod 755 /opt/myapp/myapp.AppImage

If you want a global command:

sudo ln -s /opt/myapp/myapp.AppImage /usr/local/bin/myapp

Now the binary lives at /opt/myapp/myapp.AppImage and can be launched with myapp from anywhere.

Tightening permissions

If you want only a specific group to run the AppImage:

# Create a group

sudo groupadd myapps

# Change ownership

sudo chown -R root:myapps /opt/myapp

# Restrict access

sudo chmod 750 /opt/myapp/myapp.AppImage

sudo chmod 750 /opt/myapp

Add users to the group:

sudo usermod -aG myapps alice

sudo usermod -aG myapps bob

Benefits:

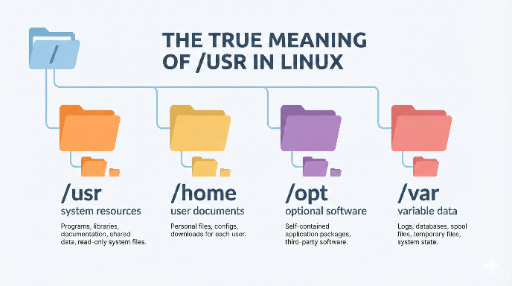

- Aligns with Linux filesystem conventions –

/optis for non‑distribution‑packaged apps. - Allows multiple users to share the same AppImage.

- Permissions can be managed at the filesystem level.

Integrating with desktop environments (.desktop files)

To make an AppImage appear in the application menu, create a .desktop file.

Example: ~/.local/share/applications/myapp.desktop

[Desktop Entry]

Type=Application

Name=My App

Exec=/opt/myapp/myapp.AppImage

Icon=/opt/myapp/icon.png

Terminal=false

Categories=Utility;

After adding this file, “My App” will show up in the menu and launch the AppImage.

For system‑wide visibility, drop the file into /usr/share/applications/.

This approach is independent of any package manager and keeps management simple.

Takeaway: The Linux philosophy in one file

AppImage embodies Linux principles:

- Transparency – you can see exactly where the app lives.

- User control – you decide where to place the file.

- Simplicity – installation and removal are just file operations.

For Windows users tired of hidden installs, AppImage offers a refreshing, portable alternative.

Once you start using AppImages:

- Begin by keeping them in your home directory if you’re just experimenting.

- Gradually move them to

/opt/<app>as you become comfortable. - Use group permissions, symlinks, and

.desktopfiles to integrate them fully.

This gives you clear visibility over what’s installed, who can run it, and how it’s organized—exactly what Linux is about.

There are no comments.