Lessons from the React RCE Incident: Why HMAC Signatures, Key Rotation, and Zero Trust Matter

What the RCE Vulnerability Showed: "Trusting Data Ends in Failure"

The recent RCE vulnerability (CVE‑2025‑55182) in React Server Components/Next.js isn’t just a headline that “React is broken.” The core message it delivers is far more principled.

"If you ever trust data sent from a client, you’ll eventually be compromised."

At its heart, the flaw was that the server used Flight protocol data (metadata) sent by the client without sufficient validation, feeding it directly into module loading and object access.

- “This value will be safely handled by React.”

- “It’s not an API we use directly, so it’s fine.”

Such implicit trust accumulated until a point where RCE was possible even without prior authentication.

The question now shifts:

- Instead of asking "Why did React get broken?", ask "What data are we currently trusting without any signature or verification?"

The answer naturally introduces HMAC signatures and Zero Trust.

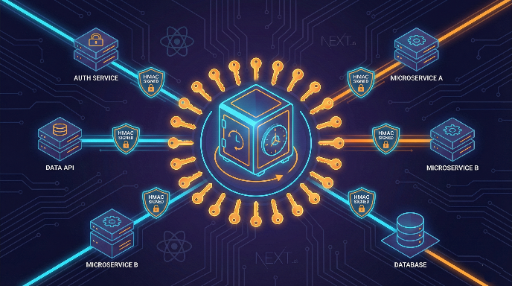

Why HMAC Signatures Matter: "Is This Data Truly From Our Server?"

Real-world systems rely heavily on inter‑server trust.

- Front‑end ↔ back‑end

- Microservice A ↔ B

- Back‑end ↔ back‑end (async jobs, queues, webhooks, internal APIs, etc.)

Data exchanged in these channels often carries assumptions:

"This URL is internal, so only our system will call it." "This token format is unique to our service, so it’s safe."

Attackers always target these assumptions first.

Enter HMAC (e.g., HMAC‑SHA256) – it answers a fundamental question:

Did a party that knows our secret key actually create this request/message?

In practice:

- Only those with the HMAC key can generate a valid signature.

- The server receives

payload + signatureand verifies: - The signature matches.

- The payload hasn’t been tampered with.

A World Without HMAC Signatures

Without HMAC, a REST/Webhook/internal API could be abused if an attacker learns the URL structure and parameters. They could craft arbitrary requests and trick the server into treating them as legitimate internal traffic.

For example:

POST /internal/run-action

Content-Type: application/json

{

"action": "promoteUser",

"userId": 123

}

Even if this endpoint is meant for back‑office use only, a breached network boundary, a proxy flaw, or exposed CI/CD logs could let an attacker impersonate an internal system.

With HMAC signatures, the scenario changes dramatically:

- The request body is signed.

- The server validates the signature on every request.

- Even if the URL and parameters are known, without the key, no valid request can be forged.

Example: Protecting Internal Actions with HMAC Signatures

Below is a simple TypeScript/Node.js‑style pseudocode.

1. Assume the server holds a shared secret key

const HMAC_SECRET = process.env.HMAC_SECRET!; // injected via .env or Secret Manager

2. Client (or internal service) signs the request

import crypto from 'crypto';

function signPayload(payload: object): string {

const json = JSON.stringify(payload);

return crypto

.createHmac('sha256', HMAC_SECRET)

.update(json)

.digest('hex');

}

const payload = {

action: 'promoteUser',

userId: 123,

};

const signature = signPayload(payload);

// Send the request

fetch('/internal/run-action', {

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

'X-Signature': signature,

},

body: JSON.stringify(payload),

});

3. Server verifies the signature

function verifySignature(payload: any, signature: string): boolean {

const json = JSON.stringify(payload);

const expected = crypto

.createHmac('sha256', HMAC_SECRET)

.update(json)

.digest('hex');

return crypto.timingSafeEqual(

Buffer.from(signature, 'hex'),

Buffer.from(expected, 'hex'),

);

}

app.post('/internal/run-action', (req, res) => {

const signature = req.headers['x-signature'];

if (!signature || !verifySignature(req.body, String(signature))) {

return res.status(401).json({ error: 'Invalid signature' });

}

// Reaching here means:

// 1) The payload wasn’t tampered with.

// 2) The request was made by someone who knows HMAC_SECRET.

handleInternalAction(req.body);

});

This pattern is the simplest way to prove that this data truly came from our side.

When Multiple Operators Exist: HMAC Key Rotation Is Not Optional, It’s Mandatory

Key rotation addresses a very real human factor.

- Operators, SREs, backend developers, contractors, interns…

- Even if not all can access

.env, the key can leak via GitOps, CI/CD, documentation, Slack, Notion, etc.

The key point is to assume the key can leak.

"We might leak the key someday."

Therefore, HMAC key rotation becomes essential.

Why Rotation Is Needed

- People change – departures, team shifts, contractor exits.

- We can’t fully track past exposures – Slack DMs, local notes, screenshots.

- Post‑incident recovery – if a key was compromised, we must be able to declare that only requests signed with newer keys are accepted.

Practical Rotation Pattern

- Versioned keys – e.g.,

HMAC_SECRET_V1,HMAC_SECRET_V2, and include akid(key ID) in headers or payload. - Server holds multiple keys – validate against all active keys, then retire older ones after a grace period.

- Document the rotation process – "Create new key → Deploy → Switch both signers and verifiers → Remove old key" as a runbook.

- Separate duties – ideally, the person who creates/rotates keys is distinct from the one who modifies application code.

When a key is a single, immutable value, key leakage equals system collapse. Rotation limits the damage window.

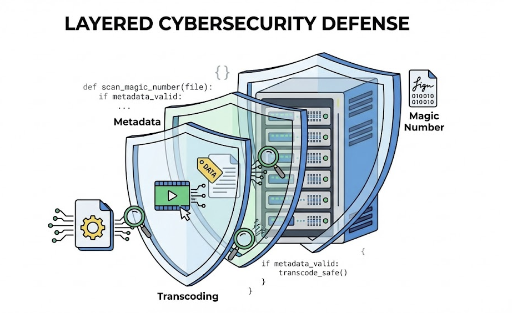

Zero Trust: "Trust Is Not a Structure, It Is Built Per Request"

The React RCE incident reminds us of a fundamental security principle: Zero Trust.

The foundation of security is Zero Trust.

Zero Trust is simple:

- Don’t assume anything is safe because it’s internal.

- Don’t assume a value is safe just because it’s used by the front‑end.

- Don’t assume a framework protects everything.

Instead, ask:

- "Did we design this input to be potentially malicious?"

- "Do we have evidence that this request came from the intended actor?"

- "How do we verify that the data hasn’t been altered?"

- "If the key leaks, what’s the scope of impact and how do we recover?"

The React RCE case fits this framework:

- Flight data was trusted because it came from React.

- The client could manipulate serialized data that directly influenced server module loading.

From a Zero Trust view, this should have been flagged as a risk from the start:

"Client‑modifiable serialized data affecting server code execution = always a risk signal."

The first line of defense in such scenarios is:

- HMAC signatures (integrity and origin verification)

- Key rotation (limiting exposure)

Takeaway: "Don’t Trust, Prove It"

Three core messages emerge:

- Never trust data by default – even framework‑internal data that traverses the network can become an attack surface.

- HMAC signatures are the baseline tool to confirm that data truly originates from your side.

- Zero Trust is the overarching philosophy – trust is never implicit; it must be established per request, per data item, and enforced through code, processes, and key‑management policies.

The React RCE incident underscores the need for a clear stance on trust in the age where front‑end and back‑end boundaries blur.

"Don’t trust; verify. Encode verification in code, processes, and key‑management. The first step is HMAC signatures and key rotation, built upon the Zero Trust mindset."

There are no comments.