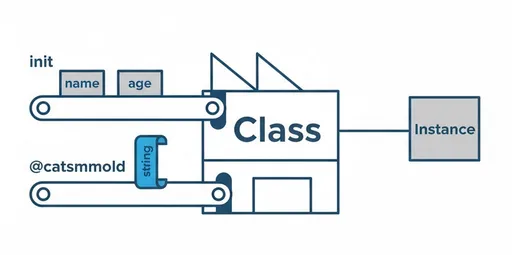

When dealing with classes in Python, you will encounter a decorator called @classmethod. This serves a unique purpose that is clearly distinct from @staticmethod and regular instance methods.

This article will clearly explain what @classmethod is, and in what situations it should be used, especially in comparison with @staticmethod and instance methods.

1. Three Types of Methods: Instance vs. Class vs. Static

In a Python class, there are fundamentally three types of methods. The biggest difference among them is what the first argument of the method is.

class MyClass:

# 1. Instance Method

def instance_method(self, arg1):

# 'self' refers to the instance of the class.

# You can access and modify instance attributes (self.x).

print(f"Instance method called with {self} and {arg1}")

# 2. Class Method

@classmethod

def class_method(cls, arg1):

# 'cls' refers to the class itself (MyClass).

# It's primarily used for accessing class attributes or,

# serving as a 'factory' for creating instances.

print(f"Class method called with {cls} and {arg1}")

# 3. Static Method

@staticmethod

def static_method(arg1):

# Doesn't take 'self' or 'cls'.

# It's a utility function unrelated to the class or instance state.

# This function only exists 'within' the class.

print(f"Static method called with {arg1}")

# Example of method calls

obj = MyClass()

# Instance method (called through the instance)

obj.instance_method("Hello")

# Class method (can be called through class or instance)

MyClass.class_method("World")

obj.class_method("World") # This is possible, but calling through the class is clearer.

# Static method (can be called through class or instance)

MyClass.static_method("Python")

obj.static_method("Python")

Comparison at a Glance

| Category | First Argument | Target Access | Main Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instance Method | self (instance) |

Instance attributes (self.name) |

Manipulating or accessing the state of the object |

| Class Method | cls (class) |

Class attributes (cls.count) |

Alternative constructor (factory) |

| Static Method | None | None | Utility functions logically related to the class |

2. Core Utilization of @classmethod: Factory Method

The most important and common use case for @classmethod is to define an "Alternative Constructor" or "Factory Method".

The default constructor __init__ typically takes clear arguments to initialize an object. However, there are times when you need to create an object through different means (e.g., string parsing, dictionary, certain calculated values).

Using @classmethod, you can create another 'entry point' that returns an instance of the class apart from __init__.

Example: Creating a Person Object from a Date String

Let’s assume that the Person class takes name and age. If we want to create an object from a string in the format 'name-birth_year', how can we do that?

import datetime

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

def greet(self):

print(f"Hello, I am {self.name} and I am {self.age} years old.")

@classmethod

def from_birth_year(cls, name, birth_year):

"""

Receives the birth year and calculates age to create a Person instance.

"""

current_year = datetime.datetime.now().year

age = current_year - birth_year

# 'cls' refers to the Person class itself.

# This is equivalent to return Person(name, age),

# but using 'cls' gives advantages during inheritance. (explained below)

return cls(name, age)

# Using the default constructor

person1 = Person("Alice", 30)

person1.greet()

# Using the alternative constructor created with @classmethod

person2 = Person.from_birth_year("MadHatter", 1995)

person2.greet()

Output:

Hello, I am Alice and I am 30 years old.

Hello, I am MadHatter and I am 30 years old. (Based on current year 2025)

In the above example, the from_birth_year method accesses the Person class itself through the cls argument. It then calls cls(name, age) using the calculated age, which is effectively calling Person(name, age) and returns a new Person instance.

3. @classmethod and Inheritance

"Why not just call Person(...), why use cls(...) at all?"

The true power of @classmethod becomes apparent in inheritance. The cls argument points to the _exact class_ that the method is called from.

Let’s assume we create a Student class that inherits from Person.

class Student(Person):

def __init__(self, name, age, major):

super().__init__(name, age) # Calls the parent's __init__ method

self.major = major

def greet(self):

# Method overriding

print(f"Hello, I am {self.major} major {self.name} and I am {self.age} years old.")

# Calling the parent's @classmethod from the Student class.

student1 = Student.from_birth_year("Jhon", 2005, "Computer Science")

# Oops, a TypeError occurs!

# When you call Student.from_birth_year

# Person.from_birth_year gets executed, and at this time, 'cls' becomes 'Student'.

# Thus, return cls(name, age) becomes return Student(name, age).

# However, Student's __init__ requires an additional 'major' argument.

The above code results in an error because Student's __init__ requires major. But the key point is that cls points to Student instead of Person.

If from_birth_year had been a @staticmethod, or had hardcoded Person(name, age) internally, calling Student.from_birth_year would have returned a Person instance rather than a Student instance.

@classmethod ensures that even when called from a subclass, it generates an instance of the correct subclass through the use of cls. (Of course, if the __init__ signature of the subclass changes like in the example above, from_birth_year will also need to be overridden.)

4. Conclusion

In summary, regarding @classmethod, we can say:

-

@classmethodtakescls(the class itself) as the first argument. -

The main use is as an 'Alternative Constructor (Factory Method)'. It's used to provide various ways to create an object apart from

__init__. -

It is powerful when used with inheritance. Even when called from a child class,

clspoints to the correct child class, allowing it to create an instance of that class.

Remember that @staticmethod is for utility functions that do not require class/instance state, @classmethod is for factory methods that need access to the class itself, and standard instance methods deal with the state of an object (self), making your code much clearer and more Pythonic.

![thumbnail of [Python Standard Library - 5] Working with Numbers: Using math and statistics](/media/editor_temp/6/b61bc8e3-5ac9-46fd-b6e2-129e91d7931b.png)

![thumbnail of [Python Standard Library - 3] Handling Time with Python: datetime](/media/editor_temp/6/5843a4cb-f3a6-4d8d-9a13-89c1cbb0ef6c.png)

There are no comments.