What a Developer Sees in an Image File: The Common “File Structure” Across Formats

From a user’s perspective, an image file is simply a picture. From a developer’s perspective, it’s a binary blob that also contains the instructions for how to interpret that blob.

In this post we’ll set aside the specific quirks of JPG, PNG, WebP, etc., and focus on the structure that appears in every image format. We’ll keep terminology minimal and explain purely from a structural standpoint.

An Image File Is Not a “Pixel Blob” but a “Byte Sequence with Rules”

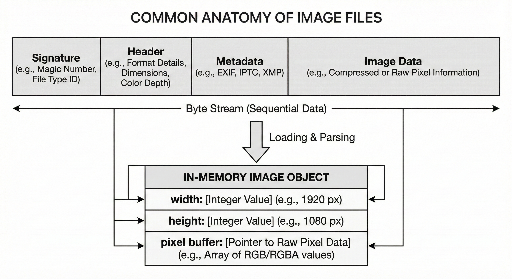

The core of an image file usually consists of three parts:

- Identity section – tells you what format the file is.

- Interpretation data – contains size, color model, and other decoding hints.

- Actual image data – typically stored in a compressed or encoded form.

While the names and order may vary, the overall skeleton remains consistent across formats.

1) File Signature: The First Hint About the File’s Identity

Most image files start with a unique byte pattern – the signature. It’s a more reliable indicator than the file extension.

- Extensions can be changed arbitrarily.

- A signature, however, is hard to forge if the file does not conform to the format.

Thus, developers determine a file’s type by inspecting the first few bytes rather than the filename.

The signature is usually only a handful of bytes, but it serves as the starting point for deciding whether to read the header.

2) Header: The Minimum Information Needed to Reconstruct Pixels

Once the format is known, the header follows. It contains the data required for a decoder to rebuild the pixel array.

Typical header fields include:

- Width / Height

- Color model (e.g., RGB, presence of alpha)

- Bit depth (8‑bit, 16‑bit, etc.)

- Compression / encoding method and any additional processing steps

The key point is that pixel data is usually not directly readable; the header tells the decoder how to interpret it. Without a valid header, even intact pixel data may be unusable.

3) Metadata: Information About the Image, Not the Image Itself

Beyond the visible picture, image files can carry extra data that isn’t strictly required for rendering but is often useful or problematic.

Examples:

- Capture time, camera settings, orientation

- Color space information

- Embedded thumbnail

- Author, copyright, and other tool metadata

From a development standpoint, metadata is:

- Optional

- Potentially affecting normal operation (e.g., orientation)

- A source of privacy concerns (e.g., location data)

Therefore, simply extracting pixels isn’t always enough; some systems must also handle metadata.

4) Image Data: Usually Stored in a Compressed / Encoded Form

The purpose of an image file is storage and transmission, so the raw pixel data is often compressed or encoded.

Common storage modes:

- Uncompressed (rare or limited use) – raw pixel values

- Compressed / encoded (most common) – transformed to reduce size

The essential takeaway for developers is:

The data inside the file is rarely a raw pixel array. Decoding is required to obtain pixels in memory.

Files are optimized for storage; pixel buffers are optimized for processing.

5) “File” vs. “Memory” Representation

Even the same image appears in two forms to a developer:

- On disk – a stream of bytes: signature + header/metadata + data.

- In memory – an object with width, height, pixel buffer, and optional auxiliary data.

Typical processing flow:

- Read the file’s front to guess the format (signature).

- Read the header to decide how to decode.

- Decode the data into a pixel buffer.

- Perform resizing, cropping, filtering, etc.

From this perspective, an image file is not just a picture but a structured, interpretable data set.

Conclusion: Reading an Image File Is Interpreting Its Structure

While each format has its own details, developers can rely on the common sequence: signature → header → (optional) metadata → image data. This order is not arbitrary; it’s a design that ensures safe and consistent interpretation.

When we say we “open an image,” we actually:

- Identify the format from the signature.

- Acquire decoding rules from the header.

- Optionally consider metadata.

- Restore the image data into a pixel buffer in memory.

Thus, an image file is more than pixels; it’s a file that carries the rules for reconstructing those pixels. Knowing this structure helps diagnose problems quickly, even in environments without a ready‑made library.

Teaser for the Next Post

- How

python‑magicand Linux’sfilecommand relate, and how they perform file‑type detection. - The practical differences between Pillow’s

open(),load(), andverify()methods, and when to use each.

Related Posts:

There are no comments.