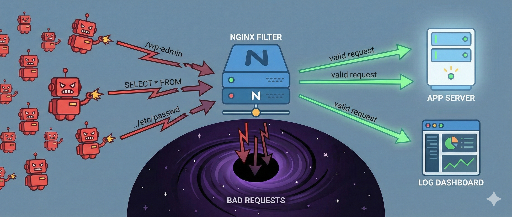

Malicious Bots Won’t Stop—Let’s Cut Them Off at the Front with Nginx: Cleaning Up Weird URLs Early

Using nginx’s blackhole.conf to tidy up strange URLs

When you expose a web application to the internet, no matter what framework you use, you’ll be bombarded with odd requests.

- Non‑existent

/wp-admin/ /index.php,/xmlrpc.phpeven if you never use PHP- Sensitive files/directories like

.git,.env,/cgi-bin/ wso.php,shell.php,test.php…

These are not your own services; they’re global scanners and bots probing for vulnerabilities. In short, any server on the internet will face them.

If your application‑level defenses are solid, most of these will be handled with 400/404 responses. The real problem lies after that:

- Log noise: legitimate user traffic gets buried under half a page of strange requests.

- CPU waste: even a tiny amount of unnecessary processing feels unsettling.

- Mental fatigue: scrolling through hundreds of

/wp-login.phpentries in the logs is exhausting.

So I prefer to block them entirely at the nginx layer—sending them straight to a “black hole” before they reach the app.

In this post I’ll cover:

- Why a first‑line block at nginx is useful

- How to manage common block rules with a single

blackhole.conffile - Practical nginx configuration examples

1. Why blocking only at the application level is insufficient

A typical approach looks like this:

- Unknown URL → 404

- Exception handling → 400/500

- Log collection → APM / log aggregator

Functionally fine, but from an operations perspective there are several pain points:

- Log noise * Error/404 ratios in APM are inflated by scanners. * You have to manually distinguish real users from bots.

- Too deep a block * A request that reaches the app has already traversed the framework, middleware, and routing layers. * It’s worth asking: Do we really need to let it get that far?

- Cumulative resource usage * A few stray requests are fine, but continuous scanner traffic can add up to a significant load.

Therefore I prefer to clean up as many useless requests as possible at the top layer.

2. Creating a black hole in nginx: immediately terminate with 444

Nginx has a non‑standard status code that simply drops the connection:

return 444;

- No response headers or body are sent.

- The TCP connection is quietly closed.

- The client sees only a broken connection.

Using this, you can drop 100% suspicious URLs without even sending a response.

Benefits are straightforward:

- The application never sees the request (zero CPU).

- Access logs can be suppressed entirely for these requests.

- The app’s logs stay clean.

3. Managing rules with a single blackhole.conf

Instead of repeating rules in every server block, keep a shared file—blackhole.conf—with common patterns.

Example:

# /etc/nginx/blackhole.conf

# 1. Hidden/config directories (.git, .env, IDEs, etc.)

location ~* (^|/)\.(git|hg|svn|bzr|DS_Store|idea|vscode)(/|$) { return 444; }

location ~* (^|/)\.env(\.|$) { return 444; }

location ~* (^|/)\.(?:bash_history|ssh|aws|npm|yarn)(/|$) { return 444; }

# 2. Unused CMS admin / vulnerability scan paths

location ^~ /administrator/ { return 444; } # Joomla, etc.

location ^~ /phpmyadmin/ { return 444; }

# 3. PHP/CGI/WordPress remnants

# Only for stacks that never use PHP (Node, Go, Python, etc.)

location ~* \.(?:php\d*|phtml|phps|phar)(/|$) { return 444; }

location ^~ /cgi-bin/ { return 444; }

location ~* ^/(wp-admin|wp-includes|wp-content)(/|$) { return 444; }

# 4. Common scanner targets

location ~* ^/(?:info|phpinfo|test|wso|shell|gecko|moon|root|manager|system_log)\.php(?:/|$)? {

return 444;

}

location ~* ^/(?:autoload_classmap|composer\.(?:json|lock)|package\.json|yarn\.lock|vendor)(?:/|$) {

return 444;

}

location ~* ^/(?:_profiler|xmrlpc|xmlrpc|phpversion)\.php(?:/|$)? {

return 444;

}

# 5. Backup/temporary/dump files

location ~* \.(?:bak|backup|old|orig|save|swp|swo|tmp|sql(?:\.gz)?|tgz|zip|rar)$ {

return 444;

}

# 6. well‑known: allow only ACME, block the rest

location ^~ /.well-known/acme-challenge/ {

root /var/www/letsencrypt;

}

location ^~ /.well-known/ {

return 444;

}

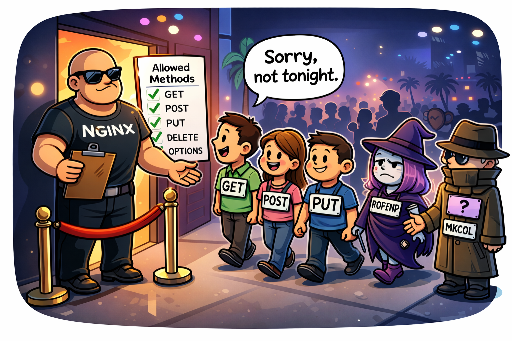

# 7. Method guard (optional): block rarely used methods

if ($request_method !~ ^(GET|HEAD|POST|PUT|PATCH|DELETE|OPTIONS)$) {

return 405;

}

Then include it once per server block:

http {

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

include /etc/nginx/blackhole.conf;

# normal routing rules…

}

}

Now most “unused path vulnerability scans” are terminated with 444 before reaching the application.

4. Optional: Suppress access logs for black‑hole traffic

If you want to keep the logs even cleaner, you can use a map to skip logging for black‑hole requests:

http {

map $request_uri $drop_noise_log {

default 0;

~*^/(?:\.git|\.env) 1;

~*^/(wp-admin|wp-includes|cgi-bin) 1;

~*\.php(?:/|$) 1;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

include /etc/nginx/blackhole.conf;

access_log /var/log/nginx/access.log combined if=$drop_noise_log;

}

}

$drop_noise_log= 1 → no log entry.- Real user traffic remains logged.

In production, start with logging enabled to verify patterns, then switch to if=$drop_noise_log once you’re confident no legitimate traffic is affected.

5. Avoiding false positives: a quick guide

The key is to avoid over‑aggressive blocking. Keep these points in mind:

- Match your stack

* If you never use PHP, blocking

.phpis fine. * If you run Laravel or WordPress, remove the.phprule. * Exclude/cgi-binonly if you actually use it. - Start with 404/403 * You can return 403 first, monitor for any legitimate hits, then switch to 444.

- Treat sensitive paths conservatively

*

.git,.env, backup files,phpinfo.phpshould always be blocked. - Order matters

* Place

include blackhole.confearly in the server block, but after any globallocation /that you want to keep.

6. Where each layer should focus

The approach described is a first‑line noise reduction. Think of each layer as complementing the others:

- Nginx black hole: cuts off obviously useless or dangerous paths early.

- Application‑level checks: domain logic, permissions, input validation—service‑specific security.

- WAF / security solutions: pattern/signature attacks, L7 DDoS, sophisticated bot filtering.

Nginx’s black hole is simple to implement, highly effective, and gives you a mental health boost by keeping logs tidy.

Final thoughts

If your service is exposed to the internet, avoiding all odd URL scans is impossible. Instead, change the mindset:

If it’s going to come, let’s stop it before it reaches the app and quietly drop it at nginx.

With a single blackhole.conf and 444 responses, you’ll:

- Clean up app logs dramatically.

- Simplify monitoring and analysis.

- Free up a bit of server resources.

The real joy comes when you open the logs at 2 a.m. and see only genuine user requests instead of endless /wp-login.php entries.

If you have nginx running, give this a try—create your own blackhole.conf, include it, and watch the difference.

There are no comments.