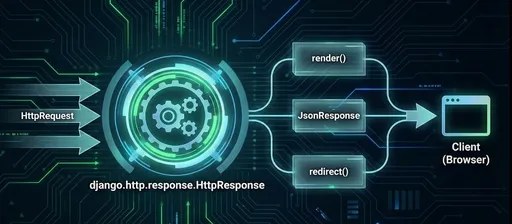

When you start developing with Django, you encounter countless shortcuts. Functions like render(), redirect(), and get_object_or_404() are invaluable for boosting productivity.

However, as you delve deeper into the source code or write custom middleware, you ultimately confront one truth: “The endpoint of a view is always HttpResponse.”

This truth, the realization that “everything ultimately boils down to HttpResponse,” comes to light at some point during your use of Django. I believe this is an important moment for junior developers transitioning to senior roles, as it involves peeling away the 'magic' provided by the framework and attempting to understand the 'machinery' behind it.

Today, I want to discuss the essence of the django.http.response.HttpResponse class, which begins and ends the Django request-response cycle, something we often overlook.

1. The Ancestor of All Responses, HttpResponseBase

The view functions we write perform complex business logic, but from the perspective of the Django framework, the duty of a view is singular: “Take an argument and return an HttpResponse object.”

Even the conveniently used render() function, when you look at its internal code, is just a wrapper that converts a template into a string and returns it in an HttpResponse.

Understanding this structure is crucial. HttpResponse inherits from HttpResponseBase, the foundation of all response classes, and everything we use like JsonResponse and HttpResponseRedirect belongs to this lineage.

2. The True Form Beyond Shortcuts

As beginners, we primarily use render, but a moment will come when we have to directly control HttpResponse.

Example: The Relationship Between render() and HttpResponse

The following two codes ultimately deliver the same HTML to the client.

# 1. Using a shortcut (common)

from django.shortcuts import render

def home(request):

return render(request, 'home.html', {'title': 'Home'})

# 2. The fundamental way (internal workings)

from django.http import HttpResponse

from django.template import loader

def home(request):

template = loader.get_template('home.html')

context = {'title': 'Home'}

# render() ultimately creates and returns an HttpResponse internally.

return HttpResponse(template.render(context, request))

Understanding the second method means you are always prepared to intervene in the framework’s automated flow, modifying headers or controlling byte streams. I believe this is why you've come across this article, as these situations where you want to intervene arise often in your mind. Welcome; let's learn together about this HttpResponse.

3. Why Should We Understand This Class?

The discussion so far is mainly a declaration that “the fundamental is HttpResponse.”

From an intermediate onwards to a seasoned developer, the reason for understanding this class becomes more pragmatic.

-

The last culprit of strange bugs is often the response object.

-

On the front end, you might hear complaints like “sometimes there are JSON parsing errors,”

-

the browser's network tab might show odd

Content-Type, -

and logs may reveal encoding issues or headers being set multiple times.

Tracking down these problems usually ends up leading you back to just a singleHttpResponseobject.

-

-

Django's “other faces” ultimately stand on the same ancestor.

-

DRF’s

Response, -

FileResponsefor file downloads, -

and

HttpResponseRedirectfor redirection

are all merely variants from the same lineage.

Once you understand the “ancestor class,” you will quickly grasp the context whenever you encounter a new Response class, thinking, “Oh, this one is just a child of that one.”

-

-

You become someone who 'extends' the framework, not just someone who uses it.

At some point, we must evolve from being someone who searches for and uses existing features to someone who creates missing functionalities and integrates them into the team codebase.-

Creating a common response wrapper for the team

-

Attaching logging/tracing information to common headers, or

-

Returning streaming responses only under certain conditions.

All these tasks can be designed much more naturally if you understand the

HttpResponseclass hierarchy. -

Common Points of Encounter in Practice

-

Custom Middleware

Middleware intercepts and modifiesHttpResponseobjects returned by views at theprocess_responsestage.

Whether it's for logging or adding security headers, it all comes down to how well you handle the response object. -

File Downloads and Streaming

When serving Excel, PDF, large CSVs, or log streams, you must pay attention tocontent_type,Content-Disposition, and encoding.python response = HttpResponse(my_data, content_type="text/csv; charset=utf-8") response['Content-Disposition'] = 'attachment; filename="report.csv"' return response -

Performance/Security Related Settings

Caching, CORS, CSP, Strict-Transport-Security, etc., are all just strings attached to response headers.

Deciding when, where, and how to attach these strings transformsHttpResponsefrom something that is “automatically created” to a “product I intentionally assemble.”

4. In Conclusion: Becoming Someone Who Deals with HTTP Beyond Django

At some point, we are no longer just referred to as “Django developers.”

With templates, ORM, and URL routing already familiar, we begin to ask ourselves this question.

“What am I really handling in this project?”

One answer to this question is the theme of this article.

What we are genuinely dealing with is not Python code, but HTTP responses.

Django is merely a massive factory for generating those responses,

and the product placed on the last conveyor belt of that factory is HttpResponse.

From the perspective of a seasoned Django developer, I view this point as a significant junction.

-

No longer just seeing

render(), but beginning to ponder, “At this moment, what kind ofHttpResponseis being produced?” -

Not stopping at “Is the template the problem?” when encountering bugs, but considering “Are the final response headers, body, encoding, and status code correct?”

-

Looking at DRF, ASGI, and other frameworks, you start analyzing “How do they ultimately generate responses?” from the get-go.

At that point, we are no longer swayed by the framework; rather, we become someone who designs how to flow data over the medium of the web.

In closing, I'd like to offer one suggestion.

The next time you write a view, consider running this thought experiment.

“If I were to implement this code without Django shortcuts, how would it look using only

HttpResponse?”

It may initially seem tedious and convoluted.

But after going through that process a couple of times, the parts you’ve taken for granted will begin to stand out.

Only then will HttpResponse no longer just be a simple class in documentation,

but rather the true face of the web application that we interact with daily, albeit unconsciously.

And a developer who truly understands that face will weather changes in frameworks much more comfortably.

No matter what technology stack you stand on, you will not lose the sense that “there is always a response at the end.”

I believe that this juncture is when we deepen ourselves as intermediate developers.

There are no comments.